Hart was born in 1901 near Delta, Colorado. As a young man he wandered around the West, accumulating the kind of experiences that would read well on a book jacket: organizing a revolt against compulsory military training at his high school in Santa Rosa, California; working as a roughneck on a southern California oil rig; canning fish in Alaska; beginning and abandoning a career as a newspaper reporter.

Whatever else he was doing, he carried a book of poetry. He studied not poems but poets, whole lifetimes of verse from the first line to the last. He marked and memorized the passages he liked best and began to ask himself by what criteria he chose them.

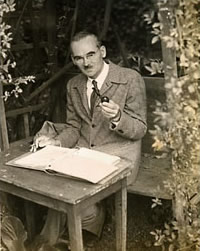

In the late 1920s, Hart settled in San Francisco. Seeking out artists and writers, he lived first on Telegraph Hill and later in the famous old “Monkey” Block at Montgomery and Kearney, a warren of studios that was the city’s informal artists’ colony. (The TransAmerica Pyramid stands there now.)

In 1934 he took a teaching post in the Emergency Education program, a New Deal venture designed to provide a bit of income for just about anybody who felt an urge to teach. He drummed up some students and began telling them how to write poetry.

Was he qualified? By his own account, not remotely.

Hart at this point was a stylistic conservative, cool to the innovations of his own time. But teaching changed his mind. Within a couple of years, he was a passionate advocate of literary Modernism. In poets like Auden, Dickinson, Eliot, Hopkins, MacLeish, Pound, and Yeats, he found a level of excitement—a skill and daring in the use of language—that exceeded almost anything in English since Milton. He sensed the same power in such Continental voices as Lorca, Perse, and Rilke. He felt he was witnessing an age of discovery. He was determined to be among the discoverers.

Hart’s genius was not as a poet—though he left a few fine sonnets—but as a passionate analyst. His method was to annotate poems, marking the passages that seemed to him to be doing the real poetic work; to type out what he had marked; and to study the resulting lists (thousands of pages in all) in the attempt to see what the writers were doing in these lines. When he thought he had identified a particular technique in use, he would describe it and ask his students to try the same. Their own new work would then undergo the same selection and study.

For fifty-five years Hart was constantly teaching somewhere in the San Francisco area: at the University of California Extension, at Mills College, at the College of Marin, in special children’s classes in junior high and high schools. But he never had more than one foot in the academic world. The heart of his work was in the private Lawrence Hart Seminars, to which the most promising of his students were invited, and which continue today.

During their heyday the participants in these seminars called themselves the “Activist Group.” Some of their successors have just recently decided to resume flying this flag.

In 1944, Hart married Jeanne McGahey, a poet he met in his classes, and moved to Berkeley, where their son John was born in 1948. In 1951, the family relocated to San Rafael in Marin County, where Hart lived, wrote and taught until his death in 1996.